A clinician’s research feats

- American Medical News

- Volume 22 • Number 30 • July 27, 1979

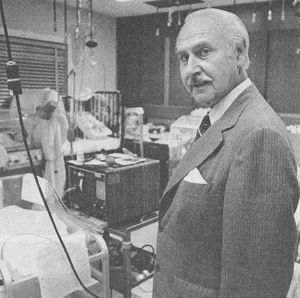

- Innovations of Orvan Hess, MD, have left a legacy of happy and grateful patients.

- Dr . Hess, developer of fetal monitor says innovations ‘went with the territory’. MD proud of obstetrics ‘firsts’

With infinite charm and patience, the Yale physician guides his visitor through the university’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, a striking building of transparent marble. The librarian is a patient woman who is eager to help.

On exhibit is “In Principio: Illustrations of the Creation Story,” and as he leafs through the priceless, rare books, gynecologist Orvan Hess, MD, 73, reflects on his lifetime of pioneering medical practice.

A man of courtly bearing, he says softly, “I was motivated to conduct research because practicing as a clinician I was dissatisfied with the care available. Nearly all my research has been directed toward meeting some need that came to light in my practice.”

He has been at Yale nearly half a century now, since he began his internship in 1932, yet this day as he walks into the bright summer sunshine, he cannot remember where he has parked his car. No matter, because there is much more to be seen on the Yale campus: the dormitory where Nathan Hale studied , the prestigious student dining clubs, statues of famous Yale people. Hours later, the car is retrieved—right down the street from the library. It is a short drive to the physician’s office at the Yale-New Haven Medical Center, where Dr. Hess has some sentimental business to attend to. He will be vi siting this day with two former patients with whom he did his early work toward developing fetal monitoring equipment.

DR. HESS never liked the “watch and wait and pray” school of obstetrics. “Physicians had to watch and wait,” he said, “because they had no way of getting the data they needed. A stethoscope just could not do the job.”

Dr. Hess decided that what was needed was a way of monitoring fetal hearts to make sure that newborns survive the traumatic period of labor and birth. By checking the fetal heart rate for signs of distress, crises could be anticipated and met. Back in the 1950s, he and Edward Hon, MD, developed a huge machine to do exactly this. Later, working with Wasil Litvenko, chief of the Yale medical school electronics library, they used telemetry to miniaturize the system.

Barbara Jean Male recalls the first machine as being “a huge contraption, about six-and-a-half feet tall by two feet wide. I was Dr. Hess’ patient, and when I became pregnant with my first child I found that my pelvic measurements were ‘marginal’ for natural childbirth. Dr. Hess wanted to use the machine to monitor my labor and delivery, and I thought, sure, why not.”

Yale only had the one monitor back in the fall of 1955 when Mrs. Male’s water sac broke prematurely at 3 a.m. and she was rushed to the hospital. For the next 24 hours, the huge machine spewed out a torrent of paper monitoring the fetal heart rate (FTR).

“WE HAD A HUGE wastebasket,” Dr. Hess recalled, “and every few minutes we’d stuff it with the printouts.” The stream of paper was telling Dr. Hess that when Mrs. Male had a labor contraction, the fetal heart rate was decelerating at an alarming rate. “It was quite severe,” he said, “dropping from the normal 140–160 beats to below 100, to as low as 60 at one point, which indicated severe distress. At the time, we did not have enough experience to determine what was causing this distress.”

Mrs. Male recalls that “They kept putting these suction clamps on my abdomen and they kept falling off. During the contractions, I could tell that the fetal heart rate seemed to be dropping, but they wouldn’t take my word for it. Had to see for themselves. Actually, I was glad to have the machine around. It took my mind off things. People were running back and forth. It was kind of like a sideshow.”

In a nearby room, Dr. Hess was pacing the floor, pondering whether or not to perform a caesarian. He had Mrs. Male wheeled into the delivery room.

The abnormal FTR prompted Dr. Hess to decide to deliver the baby early. “The child had turned in the womb,” he said, “and I had to perform a difficult mid-forceps delivery. Everything went smoothly, and upon birth we found the cause of distress: the umbilical cord was wrapped tightly around the child’s neck.”

Mrs. Male recalls that her first boy, Michael, grew up into a strapping young lad and is now a free-lance photographer, currently on assignment in Alaska. “I thought so much of Dr. Hess,” she said, “that I had him deliver my four other boys—Barry, Matthew, Chris, and Tim. We used the fetal monitor for each and every one.”

For Matthew’s birth, Dr. Hess for the first time measured intra-amniotic fluid pressure changes during contraction with an intrauterine catheter.

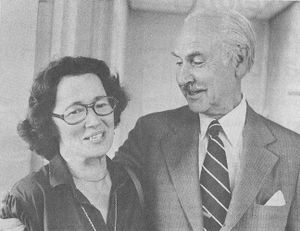

Mrs. Male, a robust, vigorous woman, is clearly after all these years still pleased with her doctor. “I guess I was a guinea pig in a way,” she said, “but I trusted Dr. Hess.” The physician replies, “As a patient she was the best. She always understood what we were trying to accomplish, and she allowed us to study her because she wanted to help humanity.” Today, the physician says softly, “a patient going through this kind of thing would probably want to sue me.”

Dr. Hess pulls from a drawer a sheaf of paper tracing another fetal heart rate—the one of the son born to his secretary, Annette McDonnell.

“MRS. McDONNELL,’’ the physician says, “was a patient on whom very early we used the fully developed technique for FTR and uterine contraction monitoring. Through telemetry, we had refined the original equipment to a much more manageable size in which the fetus’ electrical signals could be monitored and transmitted by radio signal to a distant point. Annette had already lost one baby, and she had very high blood pressure, 190/100. During her labor, there were severe decelerations in the FTR. I was unable to give her anesthesia, because of her hypertension and she delivered by natural childbirth. She was one of the first patients to have PH studies (fetal scalp), which indicated the baby was in distress (acidosis). After changing the fetal position and administering oxygen, the FTR returned to normal. She was delivered without anesthesia, and, again, we found the umbilical cord wrapped around the newborn’s neck. Her history is one of conservative management and a healthy baby delivered by natural childbirth.”

Mrs. McDonnell observes, “He was a perfect baby. In fact, he turned out to be exceptionally bright. “

Not all medical stories have happy endings. Mrs. McDonnell confides that her son, at the age of 10 while walking his bicycle across the street, was struck and killed by a speeding car.

Changing the subject, Dr. Hess points out that he has never received any financial income from his years of research , “other than for equipment and personnel help.” He began his fetal monitoring studies with the aid of $1,050 grant from the Connecticut Heart Assn. Later, a grateful, wealthy patient upon whom he had operated helped fund the study.

Before his appointment eight years ago as the full-time director of Yale’s Regional Perinatal Monitoring Program (the first time he has been paid for his research), Dr. Hess had a private ob-gyn practice in the New Haven community. He did his research, as part of his practice.

COMBINING a scientist’s astuteness and attention to detail with a diplomat’s charm and decorum, he earned a niche as the man to whom women could turn. Today, when he walks into a room, the whispers begin, “That’s Dr. Hess! Look, over there!”

But he has much more, too. A physician of rare versatility, Dr. Hess not only practices, teaches, and researches, but he widely participates in organized medicine. The senior delegate to the AMA from Connecticut, he is a past president of the Connecticut State Medical Society. When Medicaid was started in Connecticut, Dr. Hess was appointed the first director of the fledgling program. His participation on medical advisory boards and agencies runs to several typed pages.

What he is most proud of, however, he writes on a small sheet of paper. It is a list of “firsts” achieved by Orvan Hess, MD. Starting in 1933 with the first birth performed in a home by internal version and extraction, through the use of catgut—”instead of silkworm gut!”—to heal perineal wounds, through the first studies of wound healing in the uterus, to the development of the fetal monitor, and the performance of the first natural childbirth in New Haven, Dr. Hess quietly blazed a trail of clinical innovation.

“It went with the territory,” he explains tomorrow, he says, he will be going down to Cape Cod to meet with another former patient.

VACATIONING in a secluded “boat house” in Hyannis, Mass., that commands a panoramic view of the Cape is a remarkable woman who 37 years ago benefited from a true medical “miracle”—the first use of penicillin on an American patient.

Anne Miller, “Harvard by tradition and Yale by marriage” (her former husband was Yale’s athletic director), is every inch the proper New Englander, but her face breaks into a wide grin when she sees “Orvan” walking down the stairs.

She is a modest woman “and all this fuss over my good luck” tends to put her off. But she is proud of being part of one of the finest medical moments for Yale—and the world.

Dr. Hess’ role in the penicillin saga was catalytic. He was a partner of A. N. Creadick, MD, Mrs. Miller’s gynecologist. Gazing out her window at the shoreline, Mrs. Miller recalls, “I awakened one morning with a miscarriage. I had been caring for my youngest son who had scarlet fever—this was the war years and nurses were hard to find—and I contracted scarlet fever despite taking all the precautions. Within a day or two, my temperature soared to 106 and I developed severe blood poisoning.”

HYSTERECTOMY and iliac ligations were performed without relief, Dr. Hess recalled, and every known treatment including sulfa drugs—which were new then—failed to reduce the high fever. She was on death’s door when Dr. Hess suggested to Dr. Creadick that they try to obtain Gramiciden, a new drug about which Dr. Hess had read in the Reader’s Digest. The recommendation for Gramiciden led Mrs. Miller’s chief physician, the late John Bumstead, MD, and other Yale physicians to cast around for “drastic new measures.” The measure they decided on was penicillin, only recently discovered by Sir Alexander Fleming and tried on only one other person—in England.

Dr. Bumstead persuaded U.S. government officials to release 5.5 grams of the new drug for Mrs. Miller and he then convinced the patient’s husband that the penicillin must be given.

Mrs. Miller recalls that when a messenger from Merck & Co. (one of the first U.S. firms to produce penicillin) delivered the precious crystaline drug, she was not too optimistic. “The messenger wore a brown overcoat with a brown hat and brown shoes, which together with the brown bag and brown bottle he carried did little to raise my hopes.”

The little brown bottle contained about a teaspoonfull of crystaline penicillin, about half the supply available in the country. It was passed through a Seitz filter for purification and dissolved in a saline solution for intravenous injection.

“THE REST,” Dr. Hess notes, “is medical history.”

Doctors waited for a negative reaction, There was none. In four hours, a larger dose was given. Still no reaction. All other medication was discontinued and penicillin alone was administered. By midnight, Mrs. Miller’s temperature had fallen to 100 degrees. By morning it was normal for the first time in a month. Within 24 hours, her blood, which previously had shown massive bacterial growth, was sterile and remained so as penicillin therapy continued for the rest of her month-long hospital convalescence.

“After your recovery,” Dr. Hess gently nudges, “you had a chance to meet Sir Alexander, didn’t you?” Mrs. Miller recalls, “Yes, I did. I was called down to the hospital a month after my release, and there was Dr. Fleming. He was a very small man, tiny really, and he stared at me for the longest time with his enormous brown eyes. ‘You know,’ he said. ‘you really are a special patient.’

“I replied, ‘Well, yes, and I know I owe you my deepest gratitude.’ He was a very reserved man, and that is all that was said. Then he withdrew. But there was an unusually intense expression on his face as he stared at me, this woman who had made such a remarkable recovery.

“Even today, decades after my sickness, I still am amazed by it. I’ve always been religious, and I was only 33 when I got sick. I was very strong in those days. I had three young children and the Good Lord knew my work was not finished.”

It is time to go. Mrs. Miller’s cost for 60 days of lifesaving care at the Yale-New Haven Medical Center, Dr. Hess points out, was about $1,000 (hospital room and care was $10 a day and most physician charges were cancelled or nominal; a big expense was the two private-duty nurses required).

“There was,” Dr. Hess adds, “no charge for the penicillin.”

Driving through the New England countryside, Dr. Hess muses about “how I was a young man at the time of Mrs. Miller’s recovery, and a few months later I attended a medical meeting in St. Louis where they were discussing streptococcal septicemia. Well, I was just a young fellow, but I rose up and told them about our experience with penicillin in New Haven. They listened politely and, then, the moderator said, ‘That’s fine, son, now you continue with your studies—and keep us informed.’ He just brushed my comments aside.”

NEXT IS A visit to Edith Geiger, wife of the former cardiologist, Arthur Geiger, MD, with whom Dr. Hess back in 1937 started the first primitive attempts to record a fetal heart rate from the abdominal wall. Mrs. Geiger, a teacher of art and exhibiting artist, says, “Yes, Orvan, I guess I was your first guinea pig. I was glad to have you poke around my stomach trying to pick up a heartbeat. The fellow who was making all the noise, my son, is in the cabin next door.’’

The talk tonight will be more of art than medicine, but, then, Dr. Hess has always regretted that “my medical studies have kept me from improving my painting. I won an art contest once, but it took me all summer to complete the painting.”

Dr. Hess, who supremely practiced the art and science of medicine, will this month receive the AMA’s Scientific Achievement Award.

—Dennis Breo